Exchange-traded funds, or ETFs, were first developed in the early 1990s as a way to provide access to passive, indexed funds to investors. As an alternative investment vehicle to mutual funds, the ETF has continued to grow in popularity. By the 2000s, the first actively-managed ETF was launched. Although still a small percentage of ETF assets, active ETFs have gained increased interest from both investors and asset managers. As of May 2023, active ETFs represent around 6% of ETF assets1, however, they accounted for about 15% of global net inflows in 2022. In 2023 (as of May), that number has grown closer to 30%.

This blog will discuss the changes in the regulatory landscape that changed active ETF supply, the trends in the space, the emergence of semi-transparent active ETFs, and the benefits and drawbacks they present for taxable investors.

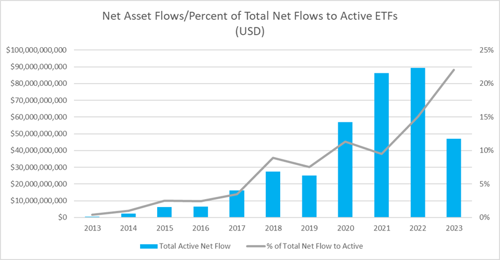

In 2008, the first active ETF was launched. In the early years, active ETFs were required to file for exemptive relief before launch, which was time-consuming, expensive, and ultimately slowed the ability to launch a new strategy. Because ETFs are not individually redeemable and do not satisfy certain requirements of the Investment Company Act of 1940, hundreds of individualized exemptive orders were required to operate. However, in 2019, the SEC announced they would replace the individualized orders with a single rule, referred to as the ETF Rule. The ETF Rule (Rule 6c-11) codified the exemptive relief, which expedited the time to launch an active ETF from several years to a couple of months. The goal of the SEC was to level the playing field among most ETFs and protect ETF investors. This led to an influx in both the creation of active ETFs and the demand from investors (the number of active ETFs grew from 325 in the U.S. in 2019, to over 1000 today3). The graph below illustrates both the net asset flows and the percentage of total net ETF flows directed toward active ETFs.

Figure 1.

Source: Figure 1. Morningstar as of 6/30/3032

Source: Figure 1. Morningstar as of 6/30/3032

Up until 2019, both active and passive ETFs were generally known for their low costs, tax efficiency, and transparency. The transparent aspect of ETFs has long been a deterrent for active managers. Holdings would have to be disclosed daily, running the risk of potential front-running. However, the regulatory changes in 2019 allowed ETFs to either disclose portfolio holdings less frequently or mask their holdings using a representative set of securities known as a proxy. These active ETFs that are not providing daily holdings are known as semi-transparent ETFs.

These changes have enabled active managers to preserve the value of their intellectual property in an ETF vehicle. Thus, many active mutual fund providers have been converting or creating an active ETF version of their existing mutual fund strategies. According to State Street, about 46 actively managed mutual funds have been converted into ETFs since early 2021, and another 16 have been announced for 20233.

Investor benefits

Active ETFs have garnered the attention of taxable investors for a couple of reasons. First, the average fee for an actively managed equity ETF was reduced to 0.38%, less than half of the 2019 level2. The other key benefit and likely the most important driver of demand is the improved tax efficiency of ETFs relative to mutual funds4. Taxable investors in the typical mutual fund structure must pay not only the capital gains tax when they exit a position but are also taxed when their funds are forced to sell positions because other investors have exited. ETFs on the other hand, can redeem securities in kind, reducing the need to sell the underlying securities in order the meet investor redemptions.

Considerations

Although there are benefits to an ETF vehicle over a mutual fund, there are considerations for investors considering semi-transparent ETFs (ST ETFs). First, ST ETFs are new and have a limited track record typically less than three years. Oftentimes, however, the investment strategies of numerous active ST ETFs are derived from established mutual funds, providing insights into how a specific strategy might have performed within a particular market environment.

Second, the bid/ask spreads tend to be more of a concern for active ST ETFs relative to fully transparent ETFs that provide daily disclosure of portfolio holdings. Active ST ETFs offer investors daily exposure to a proxy portfolio and the flexibility to trade throughout the day, but it is important to note that they typically exhibit wider bid/ask spreads. As a result, these active ST ETFs may experience elevated levels of tracking error compared to their fully transparent ETF counterparts, especially during periods of market volatility. Consequently, investors might choose to exit a position that is trading at a substantial discount to its net asset value.

Conclusion

Combining features of active mutual funds with the structural benefits of ETFs has garnered the attention of both investors and asset managers, as flows have indicated over the past few years. The hybrid approach can help investors meet their long-term goals; however, it is important to keep in mind the different sets of risks that come to play with active semi-transparent ETFs.

Sources:

Mr. Shiras is a member of Canterbury’s Research Group and is responsible for sourcing, evaluating, and monitoring traditional, long-only equity managers. Mr. Shiras serves on Canterbury's Fixed Income and Hedge Funds Manager Research Committees, and as vice chair on the Global Equity Research Committee. He also serves on the Capital Markets Committee. Prior to joining Canterbury, Mr. Shiras served as a financial analyst with Apriem Advisors, where he conducted security and economic research, and was an investment analyst with NFP Retirement, where he contributed to strategy and market research. Mr. Shiras received a Bachelor of Arts in business administration from the University of California, Irvine. He is a CFA® charterholder and a Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst.