Not all indexes are weighted equally. Some are more “equal” than others. As we have discussed in Investing in the S&P 500 at All-Time Highs, the popular S&P 500 is a capitalization-weighted index. This means that it includes companies in proportion to their size. In times when the largest companies grow disproportionately, they represent a bigger and bigger piece of the pie. This increases the concentration risk in the index. A portfolio with higher concentration is more susceptible to losses by a small number of its holdings. By contrast, there are indexes, such as the S&P 500 Equal Weight Index, that reduce this risk by equally weighting their components. This blog post will explore the current concentration risk in the S&P 500 and introduce some alternatives to capitalization-weighting.

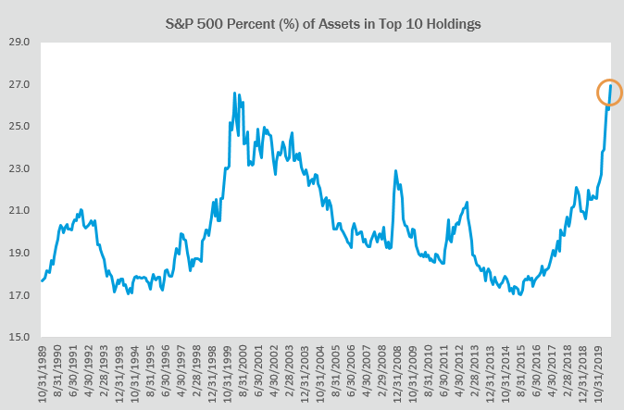

Concentration has reached a record high in the S&P 500. As of June 30, 2020, the top 10 holdings in the S&P 500 represented 27% of the index. This is the highest number since Morningstar started tracking the data in the 1980s. The index has reached this concentration level only one time in the past. It was in the summer of 2000. At that time, the largest name in the index was a familiar one: Microsoft. Microsoft, the poster child of the dot-com bubble, went into the year 2000 with a market capitalization of $600 billion. It ended the year at $230 billion (-62%) after the bubble burst, significantly dragging down the index.

Today, we find ourselves in a similar place, with concentration even higher than it was in 2000. Back then, when the market was similarly concentrated, it crashed. As larger companies gave way to smaller ones, concentration fell over the next decade, reaching a low point in 2015. For the next few years, concentration trended upward but stayed within its normal historical range.

Then, 2020 went “viral.” As the COVID-19 pandemic sent the world into a global recession, a handful of large companies grew even larger. Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google (FAAMG) all benefited as the world became more reliant on technology to stay connected. As of July 31, 2020, five stocks were up an average of 36% for the year. The entire index was up just 2%. As a result, the FAAMG stocks swelled to roughly 20% of the S&P 500.

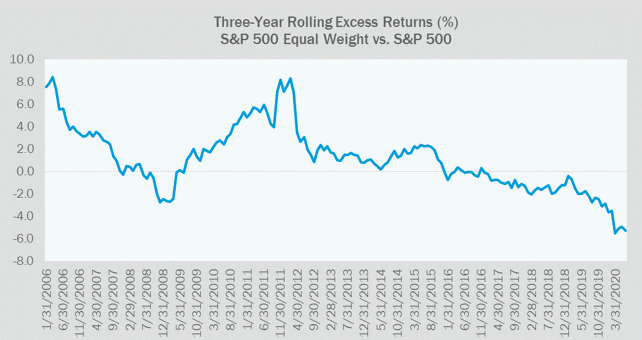

We are now in uncharted territory. Will the FAAMG stocks continue their meteoric rise? If so, the S&P 500 could become even more concentrated. Will they underperform smaller companies? Then, we might see a pattern similar to what occurred from 2000 to 2015. During this time, the S&P 500 underperformed its equal-weighted counterpart.

Since its inception in 2003, the S&P 500 Equal Weight Index has outperformed the S&P 500 by around 1% per year. The Equal Weight Index contains the same 500 stocks but assigns the same weight to each instead of weighting them by size. Thus, it nearly eliminates the problem of concentration risk. It tends to do better when gains are spread among companies and underperform in times like the current environment when performance is driven by the largest companies. This can be attractive for investors who want a diversified, low-cost portfolio that can outperform the S&P 500 in the long run.

For investors concerned about the high level of concentration in the S&P 500, what are some alternative ways of investing that still retain the benefits of indexing (transparency, low fees, diversification) while lowering the concentration risk? Besides the S&P 500 Equal Weight Index mentioned above, other alternative indexes can also be taken into consideration.

The DFA Core Equity strategy1, for example, is a broad market index that adjusts the weights of securities based on value, size, and profitability. Thus, it emphasizes smaller companies and is subject to less concentration risk than a traditional capitalization-weighted index.

The RAFI Fundamental Index2 seeks to break the link between market capitalization and weight. Instead, it holds securities based on financial measures such as sales, book value, cash flow, and dividends. The index is rebalanced to weight companies on the basis of these fundamentals and, as a result , the percentage of this index represented by the top 10 names tends to remain constant, rather than growing whenever the top names do well.

Another option would be to pair your capitalization-weighted index with an active small-cap manager. My colleague recently wrote an piece discussing the benefits of small-cap active management: Active Small-Cap Management: Long-Term Strength.

Regardless of which approach you take toward indexing, it is important to understand the risks of each. The S&P 500 has become significantly less diversified this summer. Just 10 names make up over a quarter of the index. Technology and communication services make up a third of the index. These numbers are up significantly since the start of this year. If this level of concentration is too high for your risk tolerance, it may be prudent to consider one of the more broadly diversified alternatives.

The equity strategies mentioned in this article are examples of different styles of indexes and are being used only for illustrative purposes. These are not recommendations nor are they intended to provide investment advice or represent an offer to buy or sell any security.

1 DFA Core Equity 1 is an investment strategy managed by Dimensional Fund Advisors with the objective of capital appreciation. The strategy purchases companies with a greater emphasis on small capitalization, value, and/or high profitability as compared to their representation in the U.S. universe.

2 RAFI Fundamental Index is an investment index created by Research Affiliates. The index measures the performance of U.S. companies weighted by their fundamental scores. Companies in the index are weighted using a combination of fundamental factors such as sales, cash flow, dividends/buybacks, and book value.