The steadfast stance taken by the U.S. Federal Reserve to fight the post-pandemic inflation surge continues to be a significant driver of market volatility.

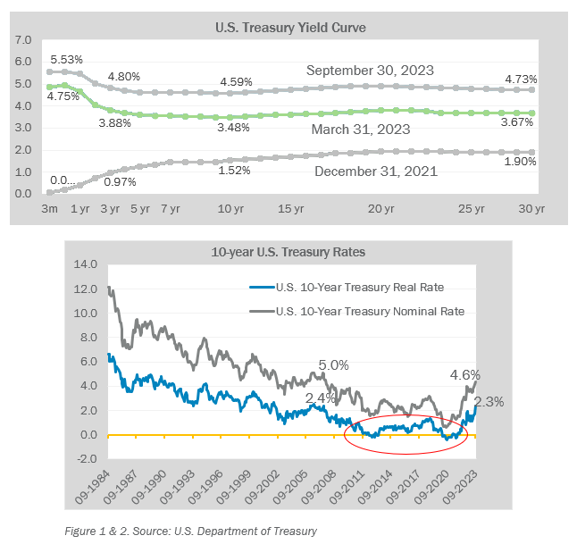

Eighteen months after the first federal funds increase in March 2022, the U.S. Treasury yield curve has shifted meaningfully along all maturities. The inverted yield curve was seen as a harbinger of a potential recession, but the economy continued to do well as global supply chains reopened and pent-up demand for travel and services drove higher levels of economic activity. Despite higher prices across most industries, companies were able to relieve supply shortfalls, the labor market has remained tight, and corporate earnings have come through for many companies. The Fed's resolve to keep rates "higher for longer" to reach the 2.0% inflation target has pushed up longer-term interest rates, including 10-year and 30-year rates, more prominently in recent months, making the yield curve less inverted but at higher absolute rate levels. Some of the volatility seen this year in growth equities, real estate, and long-duration bonds reflects the changing cost of intermediate to long-term capital. At 4.6% nominal and 2.4% real, the 10-year Treasury rate remains low relative to history, but the recent moves may signal an end to the nearly 15 years of QE-driven low nominal and sub 1% real rates. If persistent, higher real rates of borrowing have the potential to shift the risk-reward dynamics for longer-duration investments, and the challenge for the Federal Reserve is the lag time between implementing higher rates and seeing its actual effect through reported inflation numbers. Usually, by the time they see unemployment rise as a sign to reduce rates, we may already be in an economic slowdown or actual recession.

Access the Canterbury Outsourced CIO: Third Quarter 2023 Commentary